The Atlantic hurricane season lasts through the month of November, but 2017 has already been an historic year, weather-wise. Harvey and Irma are the only two Category 4 hurricanes to ever make landfall in the U.S. during the same year, and they occurred just 16 days apart. The Houston area is reeling from the aftermath of hurricane Harvey, with many experts predicting that recovery will take years. Residents of southern Florida are still counting the full extent of the devastation from Irma.

It’s difficult to comprehend the scope of these storms. For example, one report estimates that Harvey unleashed 27 trillion gallons of water on Texas and Louisiana. How do we wrap our minds around a number like that?

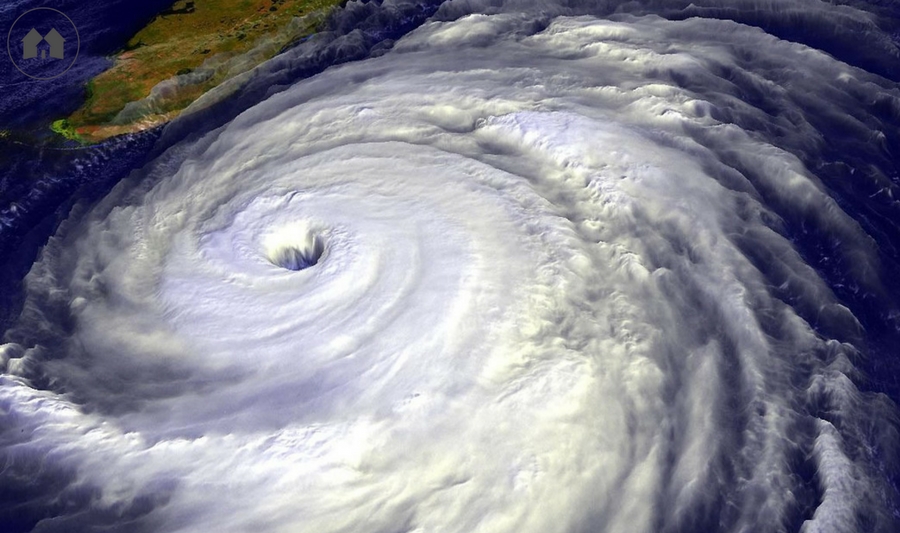

If you watched television weather forecasts (as most of us did in the days leading up to Irma), you may recall many radar or satellite images from space, including the outline of three enormous storms—Irma, Jose and Katia—swirling in the Atlantic simultaneously. Those distant images are fascinating, even beautiful in their way, but what about all the photos of raging flood waters and devastation? How do you explain those to your children?

As Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, “Knowledge is the antidote to fear.” By engaging your child’s natural curiosity, you can help him understand the mechanics of these incredibly powerful storms and in the process, you may alleviate some of his (and your own!) worries about this weather phenomenon.

What is a hurricane?

Hurricane is the name for an extremely powerful storm that occurs in the Atlantic or northeastern Pacific ocean (north of the equator). It is a type of storm known as a tropical cyclone. These storms do occur in other areas, but are called by different names. In the western Pacific (north of the equator), they are called typhoons, while cyclone is the term used for a storm in the southwestern Pacific and Indian oceans (south of the equator).

It is interesting to note that these storms spin counterclockwise if they form north of the equator, and clockwise if they form in the southern hemisphere. This is due to the Coriolis force, which is related to the earth’s rotation.

What causes a hurricane?

Tropical cyclones form when the sun heats ocean waters near the equator to a temperature of 80 degrees Fahrenheit or greater. The warm, moist air from the ocean surface rises (as hot air will do!) in a process known as convection. Most kids are familiar with the everyday example of visible steam rising from a cup of hot coffee or tea; heat is transported by upward-moving air. If your child is a skeptic, try this experiment —read the comments for some helpful tips and please use reasonable caution, especially indoors!—to demonstrate that hot air rises. (Bonus: you’ll be the coolest mom ever, at least for a couple of hours.)

Warm air rising rapidly from the ocean’s surface creates a vacuum—not a perfect one, of course, but an area of extreme low atmospheric pressure—and cooler air flows in from the surrounding area, attempting to restore equilibrium. As Aristotle said, “Nature abhors a vacuum.” It’s the same principle that makes a drinking straw work: when you draw out the air from one end, something (whether it’s air or liquid) replaces what you removed. If your child can use a straw, she’s familiar with a vacuum, but you can help her understand more fully by encouraging her to closely observe details: What happens when you block the end of the straw and draw out the air from the other end? When you unblock the end, what changes? What happens when you immerse the end of the straw in a liquid and do the same thing?

When cooler air flows in to replace warm air rising due to convection, it is heated by the water. While the air is in proximity to the ocean’s surface, the humidity rises due to evaporation. (For an easy experiment to demonstrate evaporation to your kids, click here.) In turn, the humid, hot air begins to rise. As it reaches higher elevations, it cools and forms clouds—specifically, moisture-laden cumulonimbus clouds. This cycle continues with warm, moist air rising, then cooling to form clouds, and cooler air rushing in, attempting to equalize the atmospheric pressure. The clouds increase in size and number, and the whole formation begins to spin from the Coriolis force, until there are so many cumulonimbus clouds that they form thick, swirling bands of moist air.

As the bands spin in a circular motion, a cloud-free area of low pressure forms in the center. This is known as the “eye” of the storm. Cool air from upper elevations begins to flow downward into the low-pressure center of the storm. The storm grows larger and more powerful, driven by the constant cycle of air rushing into the areas of low pressure, being heated at the ocean’s surface, then rising to become part of the swirling clouds.

How powerful are hurricanes?

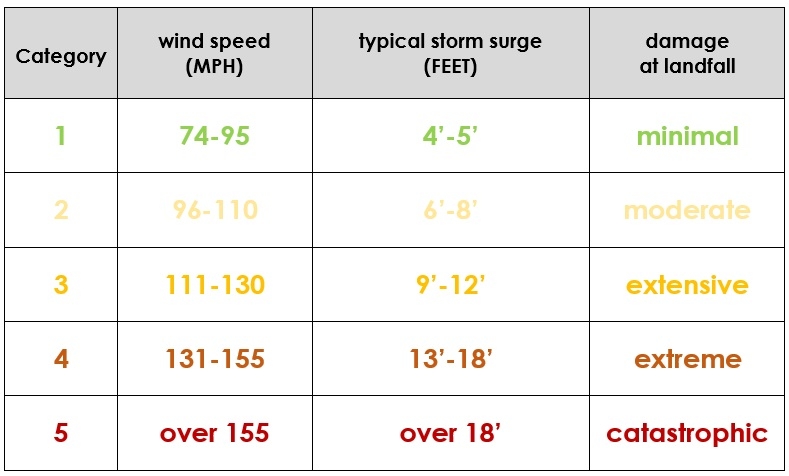

When winds (from the rotating clouds) reach 39 miles per hour, the system officially becomes a tropical storm and receives a name. Names are not assigned randomly; rather, there are predetermined lists of names that repeat on a six-year cycle. The storms are considered hurricanes only when the sustained wind speed reaches 74 miles per hour or greater.

Hurricanes are rated using the Saffir-Simpson scale, from Category 1 to Category 5:

Why are they so devastating?

When a hurricane encounters land, there are two main components of the storm that pose the most immediately danger and are capable of causing tremendous destruction: high winds and storm surge.

The threat of high winds is self-explanatory; few structures (even those designed for hurricane-prone areas) are capable of surviving the sustained winds of a major hurricane without significant damage.

In addition to the high winds that are standard in these storms, there is at least one tornado associated with almost every hurricane that comes ashore in the United States. This is especially true for those entering from the Gulf of Mexico, simply because Gulf hurricanes tend to spend more time over land than hurricanes that travel along the eastern seaboard.

Storm surge is the result of the extremely low atmospheric pressure in the eye of the storm. The air pressure is so low in the center of a hurricane that the ocean actually rises up and forms a bump where the water can be many feet higher than sea level. When the low pressure hurricane eye reaches land, the rush of water that accompanies it can be incredibly devastating.

Worst-case storm surge predictions for Irma—which thankfully did not materialize, for the most part—were as much as 15’-25’ (above sea level) upon landfall in Florida. A 15’ wall of water rushing inland is inconceivable to most of us. However, during hurricane Katrina in 2005, there was a U.S. record-breaking documented storm surge of 27.8’ in the town of Pass Christian, Louisiana.

Thankfully for those who live in hurricane-affected areas, the ferocity of the storm quickly diminishes once it reaches land and is cut off from the warm, moist ocean water that fuels it. The danger has not passed, however, simply because the storm loses power. As Harvey recently demonstrated in Texas and Louisiana, the rains from a hurricane can last many days and result in catastrophic flooding.

How do we predict and prepare for hurricanes?

Without question, the worldwide authority on hurricane prediction is NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a government agency that operates as part of the United Stated Department of Commerce. With a system of geosynchronous satellites in orbit over the earth, NOAA has constant access to weather-related images and data.

Detailed information about emergency preparedness for hurricanes and other natural disasters is available through both NOAA’s National Hurricane Center and through FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which is part of the Department of Homeland Security.

How can I find out more?

If your child is interested in learning more about hurricanes, here are some additional resources we suggest:

- The National Hurricane Center (a division of NOAA) has created an online activity in which students simulate the conditions of a hurricane. Visit the Create-A-Cane page here.

- Another activity from the National Hurricane Center allows students to “Aim A Hurricane” using wind belts in the atmosphere.

- Also available from the National Hurricane Center, printable tracking charts that can be used to plot the movement of storms.

- Discovery Education offers a hurricane lesson plan with an experiment designed to help students “discover the effects of wind speed and water depth on the height of waves in a hurricane.” (Recommended for grades 6-8.)

- The National Center for Atmospheric Research gives instructions for an experiment to demonstrate storm surge that is suitable for early elementary students.

In addition, children’s books on the subject of hurricanes can be purchased at Amazon.com or checked out from many local libraries.

If your family wishes to help those affected by hurricanes Harvey and Irma, please consider a donation to Samaritan’s Purse. Faith-based groups like Samaritan’s Purse are responsible for most of the relief efforts currently underway in Texas and Florida. Individuals or groups can also sign up to volunteer in storm-ravaged areas through the organization.

We at A Reason For Homeschool have watched the almost incomprehensible flooding and destruction in Texas, Louisiana and Florida these past few weeks. Words are inadequate to describe the shock we all feel, so we’ll simply say we hope that (most importantly) your families are safe, and continue to pray for everyone who felt the impact of these devastating storms.

Please feel free to share prayer requests in the comments below for your family, friends or loved ones affected by the recent hurricanes. We would be honored to pray for you!